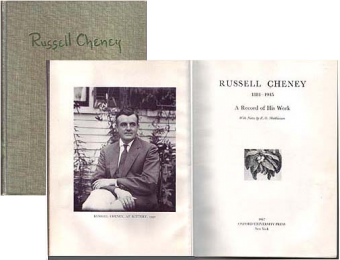

Russell Cheney: A Record of His Work. Notes by R.O. Mathiessen. Published 1947, Oxford University Press, New York

This introduction written by F.O. Matthiessen for Russell Cheney 1881–1945: A Record of his Work, was published in 1947 to accompany the retrospective exhibition Matthiessen organized to memorialize his friend.

Russell Cheney, the eleventh and youngest child of Knight Dexter Cheney and Ednah Dow Smith, was born at South Manchester, Connecticut, on October 16, 1881, and died at Kittery, Maine, on July 12, 1945.

The Cheney family, originally of Norman stock, had come to this country from England in 1635, and had located first at Rowley, Massachusetts. By the beginning of the eighteenth century they were settled as prosperous farmers near Hartford, and in 1831 Cheney’s grandfather and three brothers founded their mill for the manufacture of silk. Two of the painter’s great-uncles, Seth and John Cheney, were notable steel-engravers.

Cheney attended the Hartford High School, and followed his four brothers to Yale, where his vivid nature began to unfold and made him many solid and lasting friends. He graduated in 1904, with no special scholastic distinction, though he did a great deal of reading on his own, particularly of French history. He also nourished himself on Emerson, who prepared him to find, some years later, Whitman as his poet. While at college he spoke of being an architect, but he had already secretly resolved to be a painter. Long afterwards he mentioned shyly how one evening, while by himself in the old studio where his great-uncles had worked, he felt suddenly overcome by the beauty of a replica of the Venus de Milo and knelt in adolescent dedication at her knees. It was characteristic of him that in the midst of a gregarious family he kept his inner life almost entirely unspoken. But when he broached to his parents his desire to study art, he encountered no opposition from his father, and from his mother warm support.

He worked at the Art Students’ League in New York for three years, and then for another three years in Paris at the Académie Julian, under Jean-Paul Laurens. He felt that he had an immense amount to learn, since he had not started seriously to work until he was twenty-three, an age at which most European painters would already have been practised in their craft. He realized later that having been a student so long, he also had much to unlearn. A wholly unselfconscious openness to new experience remained with him throughout his life, and kept him young in spirit to the end.

He was president of the Art Students’ League in 1912, and began to paint in the summer with a group surrounding Charles H. Woodbury at Ogunquit, Maine. This book begins with his Paris Salon portrait in 1911 and represents all phases of his productive career. He painted in many different sections of this country, as well as abroad, and the recent facile opposition between “the American sceners” and “the expatriates” breaks down entirely in his case. He never thought of himself as anything but an American, but he wanted to master great painting wherever it was to be found. As a student he made equally absorbed copies of Manet’s Girl with a Parrot and Copley’s Mrs. Seymour Fort. Like many other Americans he loved Paris, but he did not find a strong taste for Racine incompatible with a lifelong devotion to Thoreau’s Walden.

Cheney’s work was exhibited extensively throughout the country, as well as at the Babcock, Montross and Ferargil galleries in New York. At the time of his death he was represented in museums at San Francisco, Hartford, Newark, Boston, Portland, Santa Fe, and Yale. He willed his remaining canvases and panels, about 200 altogether, to me as the friend most closely in touch with his work. My aim in making this book of reproductions, in connection with a memorial exhibition, is to let his pictures speak for themselves, as far as they can in black and white. I have selected the pictures he regarded as his best from all stages of his development. I have made no attempt to estimate his achievement, since I can still hear his chuckle as he read: “Writers on art as a rule know little of the actual problem of painting, and the best they can do is deceive a public that knows less.” That is not to say that he failed to respect a real expert like Berenson or Roger Fry.

Fortunately Cheney himself furnished the best possible kind of commentary on his work, in letters to friends, especially to Phelps Putnam and to me. From a mass of material I have selected primarily the passages bearing upon the canvases reproduced, to an exceptionally uninhibited degree Cheney wrote as he talked to his intimates. His hand-writing was very rapid, “hen-tracks on eternity,” as he once called it, and corresponded both to his lively mind and to his rich vibrant Connecticut voice. It gave permanence to the most incisive and revelatory observations on the nature of art that it has been my privilege to hear.

—F.O. MATTHIESSEN

Kittery, Maine

July 1946