Russell Cheney: Artist of the Piscataqua

By Patricia L. Heard and Richard M. Candee

This essay was prepared by the late Patricia Heard (Sep. 30, 1930–Jan. 30, 2011) for the 1996 Portsmouth Athenaeum exhibition catalog for Russell Cheney: Artist of the Piscataqua. It was expanded with new information by Richard Candee for use on this website and a large Portsmouth, NH, exhibition of Cheney’s New England paintings in 2008.

Russell Cheney was one of the first artists to bring the Modernist approach to the painting of Portsmouth and its environs. His paintings remain as fresh and undated today as when he painted them in the twenties, thirties and forties. Despite their varying styles—from the decoratively linear to a more painterly mode with rapid brush strokes—each is unmistakably a Russell Cheney. From still lifes, to portraits, to landscapes, he painted what pleased him about life, thus his paintings all have an integrity not always present in the works of more flamboyant artists. As the painter Willem de Kooning said, “There’s no way of looking at a work of art by itself: It’s not self evident—it needs a history, it needs a lot of talking about; it’s part of a whole man’s life.” This then is Cheney’s story.

Russell Cheney was the eleventh and youngest child of Knight Dexter Cheney and Ednah Dow Smith Cheney of South Manchester, Connecticut. The year of his birth was 1881 and the young Russell could well be said to have been swaddled in silk. His grandfather and his three great-uncles had founded the Cheney silk mills in Manchester in 1831 and the family led a prosperous and comfortable existence. In the words of Helen Knapp, Russell’s well-loved niece, “They practiced benevolent feudalism in a town made up of mill hands with no labor unions. They had little if any religious faith. They believed absolutely in a High Protective Tariff and the Republican Party. All of them had goodness, kindness and generosity and a sense of humor.”

Russell adored his mother, Edna Dow Cheney. His father’s absolute and tender devotion to his wife through 43 years of marriage was profound as was his parents’ devotion to the many K.D. children. It was a very close and loving family.

All five sons, including Russell, went to Yale and all became members of Skull and Bones. Russell was to prove the maverick, however, and until he came along all the other males in the family went from Yale into the family silk business. According to Helen Knapp, Russell’s parents were “startled but acquiescent” when he informed them that he wanted to make a career as an artist. It should be noted that two of Russell’s great-uncles, Seth Wells Cheney (1810–65) and John Cheney (1801–95), were painters and noted steel engravers so he, too, was following a family tradition.

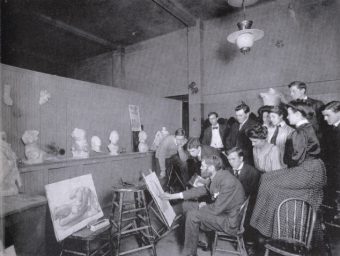

After graduating from Yale in 1904, he began work at the Art Students League in New York, studying under William Merritt Chase (1849–1916) and Kenyon Cox (1865–1919). These two men approached the teaching of art in very different ways. Cox had been a pupil of Leon Gerome in Paris, a painter who was known for his glacial classicism. Cox kept his students drawing from plaster casts for two years before they were allowed to put brush to canvas. Chase, on the other hand, taught his pupils to paint with gusto and enjoyment. Chase was a very influential figure in the New York art scene and introduced the public and private collectors to the works of Manet and the Impressionists for the first time.

In 1907 Cheney embarked for Paris where he studied under Jean-Paul Laurens at the Académie Julian. Laurens (1838–1921) was a history teacher whose ultra-realistic works strove for photographic clarity. Cheney seldom attempted this academic realism in his own work.

While he was in Paris, Cheney reconnected with his first teacher from Hartford, the Maine-born artist Walter Griffin (1861–1935), who had also studied under Jean-Paul Laurens. Griffin, who was a close friend of Childe Hassam, became a mentor to Cheney, who was twenty years his junior. In later years they were to paint together in the south of France and Cheney felt he learned a lot from Griffin. In 1930 Cheney painted a double portrait of himself and Griffin in the coastal town of Cassis now in the Portland Museum of Art. While working on the double portrait, Cheney remarked, “He’s a savage old feller, in spite of a friendly smile, and I want to get that in.”

Returning to New York after three years in Paris, he again studied at the Art Students League and became president of the League in 1909–10. Two years later, while summering in the family summer home at York Harbor, he began painting with Charles Woodbury in Ogunquit, Maine. Woodbury had started a summer school in 1898 and it ran until 1940 with a hiatus from 1917–24. In his school, Woodbury taught people of all ages and all levels of skill, a very revolutionary idea at the time. Woodbury was a brilliant teacher as well as a most accomplished artist in his own right. He taught his pupils that you don’t draw what you see of the wave—you draw what it does. Despite Cheney’s close association with Woodbury, Cheney himself seldom painted the sea by itself and only in his earliest impressionist mode depicted a landscape without people or houses. It was said that Woodbury painted with verbs; if this is true, then it can be said that Cheney painted with nouns. Cheney’s paintings have a sense of place rather than movement. He loved the tactile properties of still lifes and his landscapes have an atmospheric stillness with few scudding clouds.

Woodbury stayed in touch with Cheney and later, when Cheney was living in Kittery, came over occasionally to critique his work. On one visit in 1929, he told Cheney that his color was his weak point. Woodbury told him that he “had a weakness for cold greens in sunlight, which gave the effect of light alright, but an electrical brilliance not of the sun.” Cheney appreciated such factual criticism.

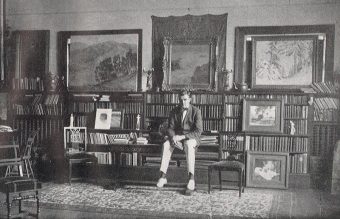

In 1916, Cheney set up his studio in a barn on his parents’ estate in South Manchester. This studio was positively palatial with shelves of leather-bound books and an oriental rug on the floor—far removed (too far perhaps) from the gritty realism of the New York art scene. In 1920 a visiting reporter described it as:

situated in a secluded spot on the large and beautiful Cheney estate. Tall pine trees are clustered about the entrance; the pathway leading to it is covered with a heavy carpet of pine needles. While it is secluded it is not separated from life there but is an essential part of it.… In a large fireplace hickory logs burned merrily and sent forth a ruddy glow which rouged the faces of Mr. Cheney and his visitor as they stood before it. It was unnecessary to explain that this was an artist’s workshop. There were paintings everywhere. They were hung in frames on the walls. They rested in racks about the room. They stood end on end and side by side on the floor, their backs resting against the walls. And from a darkened corner of the large and spacious room, one caught the glint of a cluster of marigolds and later discovered they were resting placidly upon canvas.

Russell spent almost two years at Cragmor Sanatorium in Colorado Springs, recuperating. He became enthralled with the work of Cezanne and spent hours studying his paintings.

Shortly after establishing his studio in Manchester, Cheney was diagnosed with tuberculosis, a disease that had already claimed the lives of a brother and a sister. Sent out to a sanatorium in Colorado Springs, Cheney was to spend nearly two years in bed. He spent a lot of his time absorbing a book of Cézanne reproductions and said he really learned about space and mass for the first time. When his Yale friend Phelps Putnam, suffering badly from asthma, joined him at the sanatorium, Cheney was buoyed in his isolation. Together they read the first volumes of Robert Frost’s and T.S. Eliot’s poetry and James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

Portrait of Russell Cheney by Henry Varnum Poor (1916). The painter and ceramist Henry Varnum Poor (1888–1970) and Russell were close friends and corresponded frequently. Poor visited Russell at Cragmor in 1916–17. The portrait was rediscovered at auction nearly 100 years later by Ulrich Birkmaier who recognized it from the black and white image in F.O. Mattheissen’s retrospective catalog.

After leaving the sanatorium, Cheney returned to Manchester and started preparing for his first New York exhibition at the Babcock Galleries in December 1921. His Skungimaug—Morning, included in his next New York City show at the same gallery in Nov. 1922, was later presented to the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut. The museum sponsored many of his earliest exhibitions and regularly exhibited his current work after being shown in New York. Russell later regretted that he was represented in the Atheneum by such an immature impressionist painting.

In the winter of 1923–24, Cheney joined the ailing Phelps Putnam and his wife, Ruth, at Cassis in the south of France. They were both to remain close throughout Cheney’s life. Phelps Putnam was a man with an imposing intellectual presence. In the 1920s and 1930s he was considered one of America’s most promising young poets. He was also said to be “fatally irresistible to women.” While lecturing at Bryn Mawr, Putnam met the future actress Katharine Hepburn and they fell in love. Phelps became totally obsessed with her and wrote a poem about her called “Daughters of the Sun.” When Kate’s father, Dr. Hepburn, found out about their infatuation he threatened to shoot Putnam if he seduced his daughter. In 1928, Cheney, who had a studio in New York that year, painted a strange, lost portrait of Katharine Hepburn, who they both called “The Kid.”

After he returned from France with the Putnams, Russell found himself plunged into depression. He was, after all, forty-three years old and it seemed to him and others that he had achieved very little with his talent. He was plagued by ill health, family discord, and already prone to drink too much. He had a devastating argument in September 1924 with Putnam and another Yale friend, who told him “what Griffin told him last winter in Cassis: that he must decide whether he will become an artist or degenerate into a dilettante.” Once there, he wrote, “I went to see old Mr. Griffin and to find him just back to town with a splendid crop of paintings. Hasn’t been drinking at all evidently. He’s a damn fine painter—gosh, I had a satisfactory time with him. He advised Venice at once.” He followed Griffin’s advice, and went on to Venice, the city that had proved inspirational to so many American painters.

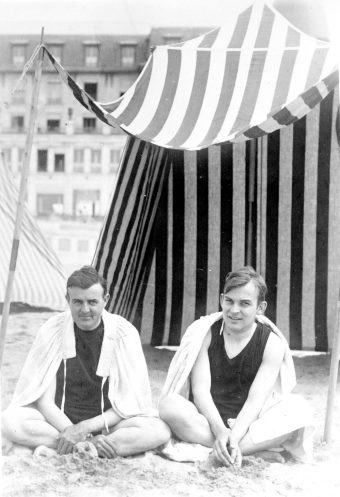

Thus it was that on the ship crossing the Atlantic in September 1924, he met F.O. Matthiessen and began the intimate friendship that would reshape their whole lives. The twenty-two-year-old Matthiessen (he preferred to be called Matty because he disliked the name Francis) was on his way to Oxford for his second year as a Rhodes Scholar at New College, having graduated from Yale. From the time they left the boat and until Cheney died, they wrote to each other almost daily whenever they were apart. They exchanged over 3,000 letters and we are fortunate that after their deaths their friend and executor Louis Hyde published many of these letters as the book Rat and the Devil: Journal letters of F.O. Matthiessen and Russell Cheney.

Both men were inspired letter writers. That Matty, who was to become one of the giants of American intellectual life, should prove so is not too surprising but few visual artists are as skilled with the pen as the brush. Cheney, whose rapid, slap-dash handwriting he himself called “hen tracks on eternity,” proved to be a lively, spontaneous recorder of his thoughts, his doings and his artistic progress. Many of his letters contain small sketches and descriptions of his current work in progress.

Russell and Matty’s travels took them through the hill towns of Italy and then on to Taormina. He painted “Greek Theatre at Taormina” in 1925.

Inspired by the new sense of meaning in his life, Cheney plunged into painting the buildings and monuments of Venice. He described himself as “singing happy” with his first painting, which was of San Marco. His Venice canvases were exhibited at the Babcock Gallery in New York the following year. He also saw Italian painting for the first time during this visit and Giotto, Piero della Francesca and Botticelli were important discoveries for him. Cheney’s keen eye spotted at once what he called the “wire-drawn grace” of Botticelli and the “firm rich modeling” of della Francesca.

After traveling with Matty through the hill towns of Italy and then on to Taormina, Cheney returned for another winter in Cassis. In retrospect Cheney wrote that the winter’s work was unsatisfactory. He felt he still needed to define his style and hold to it. After returning to the States to prepare for a third one-man show at the Babcock Galleries, he spent the summer in Normandy with Matty.

The winter of 1926 Cheney spent in Santa Barbara with his sister. He painted in the desert near Palm Springs and in a letter to Matty he describes the joys and agonies of painting. “Desert Pool comes along well.…there is the old wallop in it and how the pattern swoops around—a tight inevitable arrangement which I can get, a clear coldly luminous single light which I can’t get.…I’m a damn bourgeois imitation of an artist, that’s what I am. Pity is I know it. I could turn out such nice pictures and serve tea with them so charmingly. Balls.” Later when Desert Pool was unpacked in New York for his next exhibit he was able to write, “What a wallop when I got Desert Pool up on the wall. It has a smoldering vitality like a deep deep red geranium.”

In June 1927, Cheney and Matty began their summer life together in the southern Maine seacoast area. They first rented “The Ditty Box” in Kittery Point from Russell Smith. The following year Cheney’s niece Helen Knapp and her husband, Farwell Knapp, rented a house near them. Maine proved fertile ground for both Russell and Matty. Cheney’s 1927 painting Kittery Point [Fig. 6], exhibited at the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1933, was once in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Meanwhile, Matty started on his first book, Sarah Orne Jewett, which would be published by Houghton Mifflin in 1929. Cheney illustrated his book with three views of the Jewett House in South Berwick. The view of the front hallway is the only one of these paintings yet found. In his acknowledgments, Matty modestly credits Cheney with the three best pages in the book and also with giving him the idea of the book.

In 1928 Kittery newspaperman Horace Mitchell Jr. quoted the artist in a long interview for the Portland Sunday Transcript:

“I like Kittery Point,” he beamed enthusiastically, “It’s a swell little town.”

That was Mr. Cheney’s ancestors speaking from his lips, for they were native settlers in this part of the Country and while he himself was born in Connecticut he spent his boyhood and youth in York.

There is nothing of the “stagey” artist about him. No long hair nor flowing tie, smocks or wild looks in his eyes. No outlandish egotism that considers the existence of a lower class of humanity. And he is wonderfully blessed with an ability to show others the beauty around them…

“I do not feel everything I paint should look exactly as the original,” he explained. “But I do insist that everything I paint shall look exactly like what I want to convey. Now that one of the Lady Pepperrell house is just what I wanted. I desired to give the idea of stiff formality mixed with idealism; thus the trees have that artificial look and the garden is dreamily idyllic. That fitted my mood at the time as well as the mood of the day. On the other hand the one showing the back of Frisbee’s store has the strong sunlight that makes every line stand out like a railroad track.”

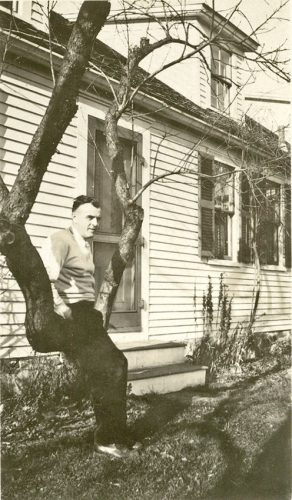

Relatives, friends and curious passersby loved looking over Russell’s shoulder as he painted en plain air.

Russell responded at once to the contrasts of the region and he painted pictures as lyrical as those of his own home, studio and garden but others portraying the harsher side of life as those of the Portsmouth waterfront. His new work from Kittery was quickly recognized for its modern, ‘primitive’ Realism. One critic in Hartford called his 1927 exhibit in Hartford, “the best exhibition of landscapes in oil that have come to this city in a very long time.” His Realism, according to T.H. Parker, was like “a mirage, in which Fords, houses, lunch-wagons and lampposts have no value pictorially, but resolve themselves into some much line, mass, plane and rhythm, which combines into compact, unified and emphatic design.… He has a peculiar chromatic scale, in which the colors generally appear all the same value. What they lack in brilliance, they make up for in delicacy, while their selection is unique.”

In 1929 Russell had another flare-up of tuberculosis and spent the winter in Santa Fe where he rented an adobe house. After visiting his sister in Santa Barbara, he was back in Manchester by April having had an X-ray that showed his lungs to be disease-free. While he was in the West he exhibited at the Museum of Santa Fe in February 1930 and at the Chicago Art Institute alongside such luminaries as William Glackens (1870–1938) and George Luke (1867–1933). These were extremely influential artists of the group known as “The Eight” or “The Ash Can School” because of their realistic subject matter. In 1928 Cheney had begun a long association with the prestigious Montross Gallery in New York and he exhibited there again in May 1930 and nearly every year or two through 1934. In 1930, too, nine of Cheney’s recent canvases were displayed at the Wadsworth Atheneum with the modernist work of younger artists Milton Avery, Aaron Berkman and Clinton O’Callahan.

1930 was also a turning point for both Matty and Russell. After a two-year teaching stint at Yale, Matty started teaching at Harvard where he is still remembered as a brilliant teacher and lecturer. In June the two men bought the Shurtleff house on Old Ferry Lane in Kittery. It was to be their most beloved dwelling place for the rest of their lives. A home of his own meant a garden of his own for Russell, always an avid gardener. His still life paintings often contain flowers painted with a loose flowing touch and glowing color.

Warm and sociable by nature, Cheney became very much part of the neighborhood. Margaret Patch remembered his small acts of kindness such as his shoveling the snow on her walkway while she was gone during a snowstorm. Nelson Cantave tells of how Cheney was instrumental in bringing his father over from Haiti to cook for him and how he afterwards helped his father get a job cooking at the Naval Prison. Cheney painted a portrait of his French-speaking houseman Cantave in the kitchen.

Occasionally gleeful with his work in progress, he was often dissatisfied and critical of his work as chronicled in his letters to Matty.

Cheney became a familiar sight on the streets of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, across the river from Kittery, and a crowd often gathered around his easel. The neighborhood boys in Kittery and Portsmouth would sit for him and one of the best-known Cheney pictures for Portsmouth people was that of Howard Lathrop, a lobsterman, painted against the background of the harbor. This painting catches the shy awkwardness of a man unaccustomed to such prolonged attention. It became part of the Portsmouth Public Library collection through the efforts of Dorothy Vaughan, a good friend of Cheney’s while she was librarian. Cheney loved giving people pleasure with his paintings. When Paul’s Market on Daniel Street, Portsmouth, opened a new shop, Cheney painted a still life of a hen and vegetables and presented it to Mr. Paul, who hung it proudly above the counter. He also painted the inside of Poore’s Greenhouse in Portsmouth.

Matty would come up from Cambridge at weekends, often bringing some Harvard friends with him. T.S. Eliot visited while he was Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard. Russell was pleased when Eliot much admired a painting of young Horace Hanlon, one of the neighborhood boys. Malvina Hoffman and Isabel Bishop, both well-known artists, came over to sketch as did Henry Varnum Poor, the potter and painter Cheney had first met in Paris during their student days. Poor painted Cheney and some of their friends and the two exhibited together several times—in San Francisco (1917), Hartford (1920), and New York City (1934). Helen and Farwell Knapp, Phelps and Ruth Putnam, Louis and Penelope Hyde were all frequent visitors and very much part of their rich and intellectual social life. Evenings were spent sitting around the dining room table after a dinner prepared by Russell, drinking wine and talking late into the summer nights.

Then there were the cats, Miss Pansy Littlefield, Pretzel, Baby and at least a half dozen more. We all know our pets are surrogate children and Russell and Matty’s affection for these animals was a shared joy. The late Richard Hyde, owner of the house and studio on Old Ferry Lane, remembered being in charge of the cats as a boy. He was paid ten cents a night to keep Pretzel in the house and five cents for Baby. If they got out there was a fine of twenty cents!

There was, however, a darker side to life. Matty was by now Senior Tutor at Eliot House, Harvard, and often felt overworked. The depression of the thirties cast a gloom over everyone. This is reflected in Cheney’s factory paintings in which no smoke belches from the chimneystacks. In the autumn of 1932, Cheney was hospitalized for an abdominal operation that, in those pre-antibiotic days, took a long time to heal. After recuperating in Kittery he went west to his sister in Santa Barbara where he stayed the winter. While in California he exhibited a two-man show with Gleb Ilyin at the Faulkner Memorial Gallery.

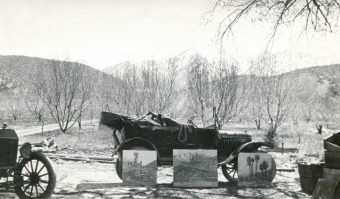

Russell had a series of “Fordies” that the mechanics at Cheney Brothers tricked out with running boards to hold his canvases.

After a busy and productive summer in Kittery, Cheney and Matty rented a house in Santa Fe for the winter and from there they toured the West in old “Fordy,” Cheney’s car. This break from the strain of teaching for Matty was good for their relationship, which was facing severe stress mainly because of Cheney’s drinking. Cheney was hitting a peak in his artistic career. In 1931, 1933, 1934 and 1936 he participated in exhibitions of contemporary New England art at the Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts. The 1934 exhibit was a one-man show of twenty-seven pictures. Most of the paintings were landscapes but for four portraits (one of Phelps Putnam) and several still lifes. This show was by way of being a retrospective of his work as it included work done as early as 1925.

The following year Cheney exhibited at the Grace Horne Gallery in Boston for the first of five annual shows. Cheney loved to paint the snow of Kittery winters, not least because the bare branches revealed their sinuous shapes. Of his preparation for a Boston show in January 1936, Cheney wrote Phelps Putnam, “I am thick in painting—just enough snow here to cover the ground and its an amazement to find how it creates subjects everywhere in places you had cruised by a hundred times and seen nothing. I suppose the secret is that the all white flat to me redraws the ground horizontal plane to me—marking it clearly off from the verticals—surely that’s what made my Triton picture by the coal wharves & schooner. I do two a day A.M. & P.M. it sounds horrible but that’s the way I am.”

That winter of 1936–37 was spent in Kittery preparing for this exhibition and a March show at the Ferargil Gallery in New York where the artist was represented for the rest of his life. His work at this time gained a clear linear quality with the buildings’ uncluttered geometric shapes depicting the local scene. As Cheney wrote Ferargil’s principal, Frederick N. Price, in February 1936, “I am fortunate in having found the right place for me to paint [Kittery] and to forget the urge to be somewhere else.… Certainly I feel now that I am fixed here for life and any work I do in other places will be more in the way of a change and tonic.” Or, as Price noted, “Gradually the appeal of the New England landscape became so strong that Mr. Cheney forgot to leave for the south after the first snow fall. He now lives and paints in Kittery all year long.”

Russell and Matty spent much of their time at their house in Kittery. A daily ritual was tea time. They served fine Hu Kwa tea to their frequent guests, still available from the Mark T. Wendell Tea Company in Acton, MA.

Yet, the dark forces of alcoholism and depression were becoming overwhelming. After his older sister married and moved to France and the “big house” in Manchester was closed, Cheney entered himself at the Hartford Retreat, a well-known sanatorium. He wrote to Matty that he was “deeply grieved for this trouble I am bringing you.” He was later able to repay his friend when in December 1938 Matty was hospitalized at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts, for severe depression. Cheney wrote to him daily, kind, encouraging letters which show how their relationship had endured as strong as ever. Cheney sent him a plant and arranged to have friends visit him; his letters are full of the doings of the cats and the small joys of life in Kittery. Matty shared with him his fight against this “obscure demon” in long analyses of the cause for his depression.

After nineteen days in McLean, Matty was considered well enough to leave but not to return to Eliot House as a resident tutor. Consequently they took an apartment at 87 Pinckney Street, overlooking Louisburg Square in Boston. This was to be a home second only to the Kittery house. Matty eventually bought the building so the cats could have free rein of the roof. Cheney produced a group of scenes of Boston and surrounding towns that were sold primarily through the Grace Horne Gallery there.

Cheney’s fine health and good spirits extended until the autumn of 1940 when he was again hospitalized for problems due to his drinking. He was also being plagued by asthma attacks and realized that he could not spend any more winters in New England. In 1943 he made the first of three visits to the ranch of his brother-in-law, General Halstead Dorey, near San Antonio, Texas, where he had exhibited at the White Museum as early as 1932. For some reason he could control his drinking far better here than when he was alone in Santa Fe. The painting he did in San Antonio was mainly stylized still lifes, often with a comic figurine and an Indian katchina in the composition. He also painted the goats that were on the ranch. His work at this time becomes much looser and at times slap-dash and unresolved. One senses that the pull on his vitality was just to stay on course mentally and physically.

One last summer in Kittery in 1944 was a happy one in contrast to the calamitous one of the year before when Cheney had been in Baldpate Sanatorium a lot of the time. Matty wrote from Toronto, where he was lecturing in October 1944: “…for the most part these months at home have shown a great gain from last year and I hope that you are going west full of a happy confidence.” The winter did pass successfully once Cheney left Santa Fe and got to the ranch in January. Once there he started painting again, gardened and listened to music. His letters are contented and full of the doings of the ranch cats but he was yearning to be back home. In a letter dated May 6, 1945, he ends, “When the moon is full again, I’ll be seeing it across Piscataqua waters with a green light and good smells of salt water.”

It was in his Kittery home by the Piscataqua that he succumbed to a massive heart attack and died on July 12, 1945.

Russell is buried in the Cheney Cemetery in Manchester, CT next to his parents and siblings. Designed as a grove around an expansive green space, the cemetery creates a peaceful and calm environment for its many permanent Cheney residents. It is a lovely place to visit.

He was buried in the family plot in Manchester. Helen Knapp, her heart breaking with the loss of her favorite uncle, accompanied Matty to the funeral where the family’s veiled hostility towards him made her feel even more protective towards this man whose whole settled life had been shattered.

Even after Russell’s death Matty continued to make sure that his reputation would survive. In 1946 the Portland Museum of Art, Colby College and even the Maine Sanitorium exhibited nearly 70 works by the late artist. Early the next year Cheney’s paintings were included in a three-man retrospective at the Institute of Modern Art in Boston, with works of Marsden Hartley who had died in 1943 and Carl Gordon Cutler who had died in 1945. Finally there was a Memorial Exhibition of Russell Cheney Paintings at the Ferargil Gallery and the Wadsworth Atheneum in 1946–47. For this Matty compiled for Oxford Press the brilliantly readable book Russell Cheney 1881–1945: A Record of His Work, an invaluable documentation of his work and a rounded portrait of the artist, mainly in his own words.

Certain painters are forever connected to a region. For his retrospective at the Ferargil Cheney was remembered as “a New England and American master.” Frederic Newlin Price said, “Cheney searched for the essence of the scene, not with his brute strength but with devoted understanding. He knew he must break the shell to have the kernel, and in his river and village scenes, portraits and flowers in the window, he presents an increasingly happy personal art.” So tied to the Piscataqua was his later work, Art News mistakenly claimed he was “born in Portsmouth, N.H.”

As we look at the Portsmouth, New Castle, York and Kittery paintings of Russell Cheney, we are not only looking back into our own recent past, we are also seeing these landscapes and cityscapes through his fond and observant eye. It was not just the beauty of the area that attracted him; he was one with its people. It is hard to think of an artist who gave away so many of his works to those who touched his life. Cheney was a regional artist in the best sense—he helps us interpret, aesthetically and historically, our own best place.

Epilogue

In 1950, Matty ended his own life by jumping from the window of a commercial hotel near the North Station, Boston. Without the sustaining love of his friend and partner, which he had had throughout his 1938 breakdown, he was unable to fight the horrors of depression. He was forty-eight years old. After Matty’s suicide, hundreds of Cheney’s remaining canvases and panels were distributed to members of the extended Cheney clan and friends or colleagues of both men, as well as to museums and universities around New England.

Bibliography

Glackens, Ira. William Glackens and The Ashcan Group: The Emergence of Realism in American Art. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1957.

Hyde, Louis, ed. Rat and the Devil: Journal Letters of F.O. Matthiessen and Russell Cheney. Hamden, CT: Anchor, 1978.

Leaming, Barbara. Katharine Hepburn. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1995.

Matthiessen, F.O. Russell Cheney, 1881–1945: A Record of His Work. Andover, MA: Andover Press, 1946.

Rosenblum, Robert and H.W. Janson. Nineteenth Century Art. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1984.

Sargent, Colin. Walter Griffin. Portland, ME: Portland Monthly Magazine, September 1994.

Stebbins, Theodore, Carol Troyen and Trevor Fairbrother. A New World: Masterpieces of American Painting 1760–1910. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1983.

White, George Abbott. The Private Letters of an American Scholar, F.O. Matthiessen. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Magazine, September–October 1978.